Brief Notes for Seminar on Remix Culture

A five day seminar took place at

Cultural Center of Spain in Buenos Aires

Florida 943

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Presented on June 17 - 22, 2006

http://www.cceba.org.ar/tapa/tapa.pl

http://www.cceba.org.ar/evento/evento.pl?evento=363

One day presentations of this seminar took place at the following places:

Waag building

Nieuwmarkt 4 1012CR

Amsterdam, Netherlands

Wanneer: June 29 2006

http://waag.org

Taller H

Humberto Primo 756

Córdoba, Argentina

August 10, 2006

http://www.tallerh.com.ar

Conference Updating Art and Technology

organized by the Troyano Collective

Centro Cultura de España en Santiago de Chile

Santiago, Chile

August 19, 2006

http://www.t-r-o-y-a-n-o.cl

Part of my theory was presented in relation to my online art practice at

Berliner Technische Kunstschule (BTK)

Berlin, Germany

June 22, 2006

http://www.htk-berlin.de/index.html

http://www.liquidvideo.de/index.php?page=22_Juni

| This page presents images that are relevant to the lectures listed above. More specifically, it is meant to complement a summary of my five day seminar published online by CCEBA. To learn how concepts of remix apply to new media projects, please visit remixtheory.net (coming soon). |

Brief introduction to Remix:

Generally speaking, remix culture can be defined as the global activity consisting of the creative and efficient exchange of information made possible by digital technologies that is supported by the practice of cut/copy and paste. The concept of Remix often referenced in popular culture derives from the model of music remixes which were produced around the late 1960s and early 1970s in New York City, an activity with roots in Jamaica’s music. Today, Remix (the activity of taking samples from pre-existing materials to combine them into new forms according to personal taste) has been extended to other areas of culture, including the visual arts; it plays a vital role in mass communication, especially on the Internet.

I argue that the remix, as it is understood today, starts with the hip-hop DJs of the 1970s because they appropriated the turntable, an electronic device designed strictly for listening, and turned it into an instrument of creative and political action; they went beyond what the Disco DJs had done with their longer mixes. The hip-hop DJs saw the turntable not as a remixing tool but as a musical instrument with which they could create unique sounds such as scratching. I argue that the hip-hop DJs play an important part in the cultural shift from a passive consumer model to a consumer/producer model, which is currently in place throughout the Internet, and is most evident in the blogger.

|

DJ Cool Herc

(Introduces Toasting in NYC)

throughout the seventies

|

Grandmaster Flash

(Hacks the DJ mixer)

Mid to late seventies |

Afrika Bambaataa

(Plays with the possibilities of sampling)

Mid seventies to early eighties

|

Rane Mixer

(A late model following Granmaster Flash's hack) |

The Hip hop DJs improved on the skills previously developed by Disco DJs starting in the late sixties. They took beatmixing and turned it into beat juggling, which means that they played with beats and sounds on the turntable to create unique momentary compositions. This is known today as turntablism. This practice found its way into the music studio as sampling, and is now extended in culture at large with the use of computers as the practice of cut/copy and paste. |

| There are three types of remixes that are currently at play. These crossover and blur their own definitions. Based on a materialist historical analysis, it can be noticed that DJs became invested in remixes which in different ways had already been at play in culture at large. Below are brief definitions with visual examples. (This is true except for the first form of remix--which was a direct reaction to brief versions of diverse popular material--see definition below. Also visit remixtheory.net for details.) |

The first remix is extended. This was actually the first form of remix in which DJs became invested. Instrumental sections of dance records were made longer for better mixing in the night club by Disco DJs during the mid-seventies. On close examination this was a reaction to the status quo in mass culture, where everything was made as brief as possible, from radio songs to novels. A popular example of this tendency is Reader's Digest. |

|

|

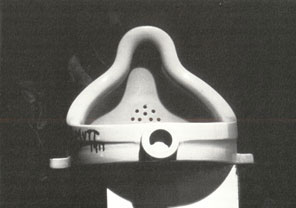

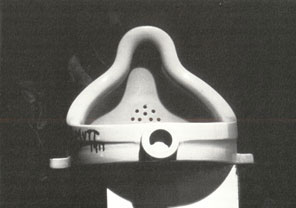

The second remix is selective. Here the DJ takes and adds parts to the original composition, while leaving its spectacular aura intact. A visual example is Duchamp's urinal: it being a urinal is left untouched to reinforce the question, what is art? A second level remix on Duchamp was done by Sherrie Levine; she questions Duchamp and his urinal, while leaving intact Duchamp's aura--but not the Urinal's. Why this is necessary is explained in detail in Remixtheory.net (coming soon). |

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain

1917 |

Sherrie Levine

Fountain

(After Marcel Duchamp)

Bronze

1991 |

| A second example of the selective remix can be found in DJ culture itself. Notice how the CD remixer gains authority by allegorizing the turntable. |

Technics 1210 |

Technics SL-DZ 1200 |

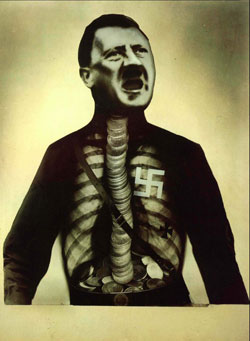

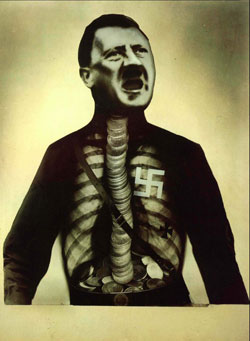

The third Remix is reflexive. It takes parts from different sources and mixes them aiming for autonomy, yet the spectacular aura of the original(s) whether fully recognizable or not is necessary in order for the remix to have cultural acceptance. An example of this is John Heartfield, who takes material out of context to create social commentary. The spectacular aura of the source image (like in the second remix) is left intact, but gains access to social commentary when combined with other recognizable images. |

John Heartfield

Hurrah, the Butter is All Gone

Photo Montage |

John Hartfield

Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk

photo- montage |

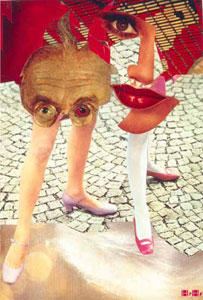

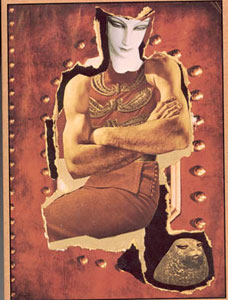

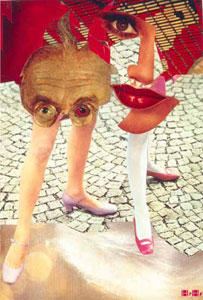

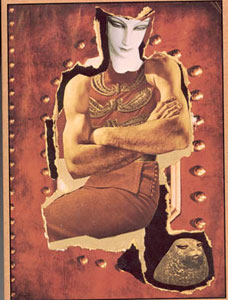

Another example of the reflexive remix is the work of Hannah Hoch. Her collages blur the origin of the images she appropriates; the result is open-ended propositions. Her work often questions notions of identity and gender roles. Yet, even when it is not clear where the material comes from, her work is still fully dependent on an allegorical recognition of such forms in cultural at large. |

Hannah Höch

Grotesque

1963 collage |

Hannah Höch

Tamer (1930)

collage |

| There are many other examples from art history and popular culture which can be presented. The above examples have been chosen based on feedback received throughout my research during my last year at UCSD. Neo-dada material by Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and their contemporaries can be connected to the reflexive remix, while work by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein can be related to the selective remix. The extended remix, however remains unusual, except in the club remixes. Why this is so is entertained in detail at Remixtheory.net. (coming soon) |